[ad_1]

The Ukraine conflict and the resulting sanctions on Russia have had a major impact on the international diamond industry. ROBERT BOUQUET analyses the effect on the distribution pipelines and what’s in store for the jewellery sector.

Over the past two years and during the pandemic I had predicted the diamond industry would recover to much better times as economies revive, consumer spending accelerates and demand for the one product that provides the ultimate expression of love matches the level of emotional response and outpouring that the world understandably feels the need to make after COVID-19.

It was only three months ago I concluded that I was excited by 2022. The industry had a lot of opportunity in front of it, mining companies were facing a potential bumper year and the trade must be careful in maintaining margins throughout the pipeline.

Even though the diamond industry was facing a rosy period, I also noted that it faced risk on the macroeconomic side, including geopolitical threats between Russia and the West over Ukraine. I also noted seemingly worsening relations between China and the West and increasing energy costs.

I concluded by saying: “Hopefully, none of these issues will destabilise the positive momentum of the diamond industry; but these are areas of risk.”

Well, there is no doubt that times have changed.

The current state of play

At the time of writing, the diamond industry is in a confused state. In recent times the rough diamond segment has boomed with continuously rising polished prices, diamond jewellery retail sales surging in the US and recovering in China; marginal diamond miners performing much better against a backdrop of seemingly constantly increasing rough prices.

And yet even though we operate in a unique, exciting and often dazzling business, we must always remember that the diamond industry is not immune to external economic and geopolitical pressures.

Alrosa is the world’s largest producer of rough diamonds (by carats), producing around 32m carats per annum, which equates to about 30 per cent of the world supply. It has the world’s largest diamond reserves (over 1bn carats in the ground). The Russian company is expected to stay in ‘pole position’ as the largest producer for many years to come.

While there are a number of mining companies operating in Russia, Alrosa produces more than 90 per cent of all diamonds. Alrosa also has diamond mining projects in Angola and exploration development in Zimbabwe, but the current focus is very much on diamonds being exported from Russia.

Alrosa is owned 33 per cent by the Russian government, 33 per cent by the Republic of Sakha (in the far east of Russia, where most of the Russian diamonds are mined) with the balance being traded on the Moscow Exchange (Russian stock market).

At the end of February, Alrosa’s share price fell to a low of 68.00 rubles ($US0.62) compared with the 12-month high of 150 rubles ($US1.37).

The Russian invasion of Ukraine has created an extremely volatile and unpredictable situation. It’s a situation that is certainly out of the hands of the diamond industry itself. People are dying in Ukraine and for some worrying about the diamond industry may seem trite.

At the time of publication, sanctions have been further strengthened against Russian diamond interests. The first step was sanctions imposed on both Alrosa and its CEO. The initial sanctions were designed to reduce Russia’s ability to finance its military operations; in Alrosa’s case specifically to ‘prohibit transactions and dealings by U.S. persons or within the United States in new debt of longer than 14 days maturity and new equity.’

This meant that Alrosa was initially prevented from raising funds over a period of more than 14 days. But what did this mean in practice?

It actually meant that the sales of rough could still take place; and sales are still taking place. Some transactions are being made in alternative currencies such as rubles or euros – this was an option that Alrosa had been previously considering offering to its clients anyway.

Rough diamonds can be shipped using different methods and routes, even looking for more ‘friendly’ transit points.

However, Alrosa is not able to raise equity, or cash and debt for capital investments such as mining project development. However, this is an issue for the longer-term, and not the immediate future.

The shipping of polished ‘on memo’ is also hampered; but this is not a major component of the Russian diamond trade and is more of a longer-term issue anyway, if it’s at all significant.

Many people within the diamond and jewellery industry, as well as those external to it, are asking: “Should the entire global trade of all rough from Russia be blocked immediately?”.

It is actually hard to see how it can be fully stopped globally; and who would actually make that decision. This is a truly multinational industry.

Polished versus rough

|

|

Alrosa’s gem-quality stones which also include a 242-carat rough. |

Rough diamonds have Kimberley Process (KP) certificates and therefore have clear provenance (for their first export) of origin and a chain of custody; most polished diamonds do not. I will come back to polished diamonds later, but first let me address the matter of rough.

Probably the only workable mechanism, if the industry chooses to act, is to use the Kimberley Process to stop issuing certificates for rough diamonds, which would therefore stop the ability for anyone to export rough diamonds to any country outside of Russia.

At the time of writing, that decision had not been taken, as far as I am aware.

Although I suspect that a KP ban on Russian diamond exports might be being discussed behind closed doors already it will certainly require international agreement by the participating member governments of the KP if this next step in blocking Russian diamonds is indeed going to happen.

Other diamond producers might see the current situation as an opportunity to increase prices for their non-Russian goods and lobby for a ban on Russian rough. This may well be happening behind the scenes. It has been said, never waste a crisis, and that is true when it comes to your competitor!

The lobbying will certainly be happening in the spheres of the far more influential oil and gas producers globally. To put things into some sort of perspective, Russian rough diamonds might equate to $US4-5 billion in a good year; this is minimal in comparison to Russian oil and gas.

Russia is among the world’s largest producers of both crude oil and dry natural gas – and the figures relating to these industries dwarf the diamond industry by comparison.

Typically, Russian oil exports account for triple the amount of revenue compared to its gas. Logically Russia will seek new markets for its oil and gas, China being one obvious option. Supply shortages, high levels of inflation and recession, and maybe even economic depression are potentially at play here.

Therefore, while Russian diamond exports are nowhere near oil and gas, they are not unimportant; diamond exports is still a large number for the industry itself and in the wider sanctions issue – especially for what is ultimately a nonessential, luxury item.

The second development that has happened is an executive order issued by the President of the United States prohibiting the import of ‘non-industrial’ Russian diamonds.

This is a more direct attempt to stop the flow of Russian diamonds into the US, however as with all these things, it is not so straightforward. It is important to understand the practicality of this move.

Firstly, very little Russian rough actually makes its way directly to the US. There is minimal rough trading there, and very little diamond polishing. For example, only the very best stones might be polished in New York.

So the ban on what is in effect less than one per cent of Alrosa’s revenue is more symbolic than consequential. To give a perspective here, 35 per cent of Alrosa rough sales are made in Europe (Antwerp in Belgium is a major rough trading centre).

Polished is more complicated; the US is the largest consumer market for diamond jewellery at around 40 per cent of global diamond jewellery sales. Therefore, Russian diamonds – remembering that Russia accounts for 30 per cent of the annual international diamond production – certainly end up in US retail stores and on the fingers of American women.

Yet, with few exceptions, polished diamonds are untraceable back to their origin, which means it is difficult to see how the US President’s executive order can work in practice.

The trade may seek to avoid ‘Russian’ polished however around 95 per cent of the world’s diamonds are polished in India and cannot necessarily be identified as being produced from Alrosa rough.

The industry is watching carefully as things develop but it is clear that the only truly effective way to impact the Russian diamond industry is to stop the flow of Russian rough with a global block on its movement.

|

||

| Alrosa’s Jubilee pipe in in Yakutia, northeast Russia. |

|

|

|

||||||

| ‘The Spirit of the Rose’ is Alrosa’s prized polished pink diamond that sold for US$26.6 million at a Sotheby’s auction. The 14.83-carat Type IIa Fancy Vivid Purple-Pink diamond is internally flawless and cut from a 27.85-carat rough. | ‘The Spectacle’ is Alrosa’s largest polished white diamond. The 100.94-carat rectangular step-cut diamond was sold at Christie’s in May 2021 for US $14.1 million. | Alrosa named a 91.86-carat yellow-brown rough diamond ‘Kyndykan’ after a young indigenous female heroine who symbolises resilience and spiritual strength of the people of Yakutia. | ||||||

The market reacts

So if we look at how the trade is reacting to these developments the first thing that seems to be happening is an immediate sense of market uncertainty. And all markets hate uncertainty!

The rough market was very strong before the Russian invasion of Ukraine. In some cases prices had doubled (or even more) in certain categories, but now it has taken a jolt back.

It should be said that the rough market was overheating anyway and had to contract at some point, so the conflict in Ukraine has coincided with an expected contraction. That said, readers should be aware that rough prices are still extremely high. Despite an average price drop of 20 per cent (seen at some market sales events in the past few weeks) many diamond categories remain at near-record highs.

Today, not only are we dealing with non-typical market forces, but also a potential major global military conflict. I expect that significant market and trading volatility will remain for some time.

Additionally, there is uncertainty over the speed of deliveries from Russia, and increased market nervousness. Right now, I still expect much of the Russian rough to reach the international trading and cutting centres, if not necessarily at the same price levels. It really is a very unpredictable time.

Given the huge worldwide backlash against Russia – with many companies, including global luxury brands, ceasing their activities there, or shutting up shop (temporarily, hopefully); or boycotts on Russian products, for example vodka being removed from supermarket shelves – one has to wonder how diamond sales at a consumer level will be affected.

Polished diamonds originating directly from Russia have been banned by the US, but nowhere else. Again this is a small part of the global diamond trade.

As I have previously noted, most polished diamonds do not have clear provenance. While some manufacturers and retailers, such as Tiffany & Co., have clear chains of custody and can guarantee the origin of their polished stones; most traders, wholesalers, jewellery manufacturers and retailers cannot provide these guarantees. That is just a fact.

And so, if the industry wants to try to self-regulate and stop Russian origin polished, I can’t see how this could be implemented. If the consumer refuses to buy Russian polished and demands non-Russian diamonds, the only option is to buy from those retailers or traders who can explicitly prove provenance.

The largest risk is that consumers simply refuse to buy any diamonds due to lack of provenance from most sellers, however, at this point, I cannot see that happening.

There will also be the economic cost caused by this global instability, which is bound to impact on luxury spending. With fuel costs hitting record highs and inflation on the rise, I expect that consumer spending is sure to be impacted in the short term and we will very likely see a contraction of spending on luxury items, diamond jewellery included.

What next for the diamond industry?

While the conflict in Ukraine continues there is a risk of a downturn, including reduced consumer spending. It is possible that 30 per cent of the world’s supply may be boycotted, which could benefit the suppliers of the remaining 70 per cent.

I must say, this was not how I foresaw a modern, competitive 21st century global diamond industry existing and operating. Did anyone?

The level of uncertainty around the world offers a conundrum: at the same time rough and polished prices are at record highs and luxury spending was booming as the world ‘exited’ the pandemic; for now our industry still shines brightly. Diamond mining and manufacturing does a lot of good around the world and brings a lot of joy to millions of people.

History shows that it always bounces back after global setbacks.

We shall have to wait and see what happens next. Once the Ukraine conflict is over – and hopefully it will be soon and doesn’t worsen – there will always be other macro-economic challenges for the diamond industry to navigate, but hopefully the world will be on a firmer and less troubled footing.

|

|

|

|

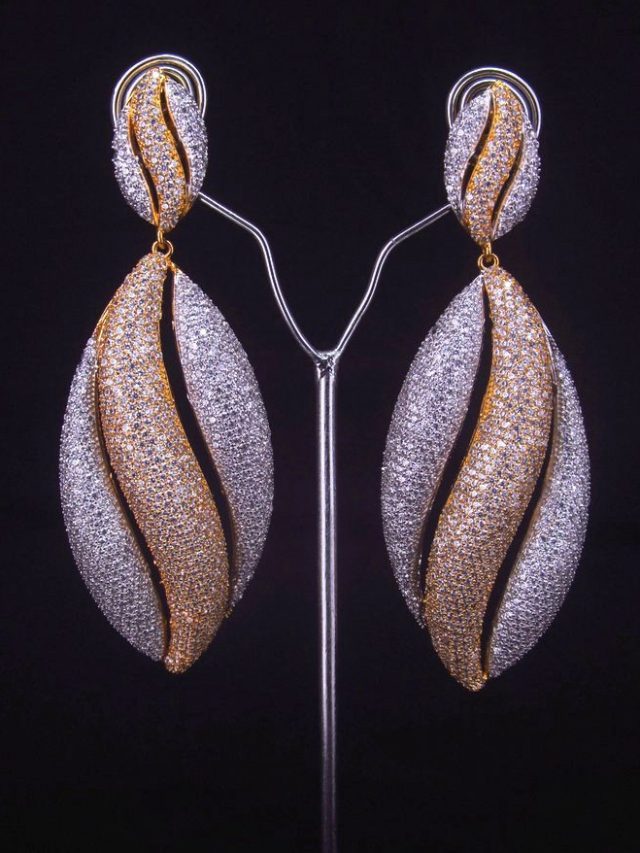

| Luminous Diamonds | Carl Faberge | Heritage Collection | |

|

|

|

|

| Alrosa ‘Imperium’ Collection | Alrosa ‘Moonlight inner drive’ bracelet | Alrosa ‘luminous’ collection pendant | |

[ad_2]

Source link