[ad_1]

Arabella Roden explores how the white metals category is adapting to an unpredictable market, and what the future holds.

As a jewellery category, white metals – platinum, palladium, silver, and white gold – are impacted not only by consumer demand, but by a complex interplay of macroeconomic factors.

The disruption of the COVID-19 pandemic to global supply chains – particularly in the mining sector – as well as investor confidence and lowered demand from the automotive sector, have all led to some volatility in the white metals market.

“Having suffered steep falls in early 2020 as result of the global COVID-19 outbreak, precious metal prices rebounded strongly in the second half of 2020 as the pandemic triggered stockpiling by investors looking to protect their wealth,” explains Richard Hayes, CEO The Perth Mint.

“This, alongside supply deficits, pushed gold prices up by 25 per cent last year, while silver rose 47 per cent, and platinum and palladium by 11 per cent and 23 per cent, respectively.”

Hayes notes that precious metal prices “again trended higher in early 2021 on a more optimistic economic footing, before retracing markedly” as a result of economic policy changes and the Delta variant of COVID-19.

White metal jewellery demand has followed a similar pattern, with the initial shock of the pandemic waning around July of 2020 before a sustained period of growth, later interrupted in mid-2021 by the Delta variant and associated lockdowns across NSW and Victoria.

Still, as a diverse category comprising premium priced platinum, palladium and white gold and affordable silver, white metals have widespread appeal as well as a competitive advantage in the high-value bridal sector – though this too has experienced recurrent disruption as a result of the pandemic.

Platinum progress

Platinum prices reached a five-year high of $US1,266 per ounce in February 2021, rising steadily following a plummet in March 2020 to the lowest level since 2003.

Still, platinum prices remain significantly below that of gold, palladium, and rhodium – all components in the manufacture of white gold jewellery.

Rhodium in particular has experienced a “phenomenal price movement” since January 2019, according to UK resources firm Johnson Matthey, rising from $US2,300 to $US29,200 per ounce in March 2021; since May, it has plateaued at approximately $US15,000 per ounce.

Chris Botha, innovation division manager at Palloys, observes, “Platinum pricing has had a continuous run for some time, and while it has slowed a little, jewellers will be weighing up the additional labour costs of working in platinum against rapidly having to purchase rhodium plating.

“The rhodium market is very volatile and has seen steep increases in pricing over the last 18 months.”

Like palladium, South Africa is the largest producer of rhodium. It accounts for 80 to 90 per cent of total global production, which was significantly reduced by temporary mine closures last year, with the overall ‘rhodium deficit’ – the gulf between supply and demand – more than doubling.

The unprecedented upward pressure on rhodium prices is largely from the automotive sector, with manufacturers in China and Europe utilising the metal to reduce emissions.

The automotive sector has also buoyed platinum prices, in tandem with jewellery demand and disrupted supplies, Hayes notes.

According to the World Platinum Investment Council, jewellery demand for the metal recovered by 22 per cent in the first quarter of 2021 when compared with the same period in 2020, driven by China and the US.

In April 2021, the Council predicted the overall platinum jewellery market would recover the ground lost in 2020, rising 13 per cent.

Industry organisation Platinum Guild International (PGI) tracks demand for platinum jewellery across a number of retail chains in the key markets of the US, China, Japan, and India.

Commenting on its first-quarter report, Huw Daniel, CEO PGI, noted that while jewellery demand could “slow in some markets as subsequent waves of COVID-19 cloud the outlook”, there had been “a renewed enthusiasm for platinum” within the jewellery industry.

“Jewellers are increasingly engaging with this precious metal, which has been effectively marketed as a metal of meaning and become important as consumers look for ways to symbolise and mark occasions in restricted and unprecedented times,” Daniel said.

Indeed, platinum sales across PGI’s key markets were driven by targeted campaigns promoting branded platinum collections. In India, historically a far stronger market for yellow gold, retailers who took part in PGI’s ‘Platinum Days of Love’ campaign reported a 17 per cent increase in platinum sales in the first quarter of 2021.

Locally, Greville Ingham, national sales manager at Peter W Beck, observes, “The family of white metals has seen popularity recently and we have especially noted a great demand for platinum jewellery, in both men’s and ladies’ wedding rings.”

Ingham noted two factors increasing the demand for platinum: “Platinum is perceived as a rare and more exotic precious metal, so the current relative affordability has made it accessible to those who may not have previously considered it,” he explains.

“The second factor drawing customers to platinum is the qualities of high purity – platinum being a hypoallergenic metal and a naturally strong white colour without the need for plating.”

Ingham adds, “In terms of the white metal market, the relative price difference of platinum to white gold has lately made platinum a popular choice. We see that this pricing will be an influencing factor for some time.”

At Chemgold, director Darren Sher has observed “a slight increase in 9-carat and 14-carat white gold as well as platinum being ordered – this of course due to the higher palladium cost pushing up the cost of 18-carat white gold.”

Sher adds, “Overall, the price increase in palladium has resulted in customers utilising lower-carat white gold as well as platinum quite often; however, having said that, the majority of our clients prefer 18-carat white gold or platinum for the white metal jewellery.”

Showing the strength of white metal demand, Botha told Jeweller, “Our sales data shows the spread of sales in 18-carat golds to be 50 per cent yellow gold, 35 per cent white, and the balance rose gold.

“However, by weight value if we add platinum – which nearly matches yellow gold for sales – definitively, the white metals are selling better.”

In refining terms, the figures echoed the sales data with Botha noting “increases in white gold and platinum refining, with sporadic large bursts of platinum refining, as jewellers opt to save more of the white metal until there is enough for a larger refining job.”

He added, “Our sweep and four-metal recovery services have seen a significant increase as jewellers want to recover the palladium and platinum from their small lemel and sweeps.”

At Chemgold, demand for both two-metal (gold and silver) and four-metal (gold, silver, palladium, and platinum) and platinum refining had remained stable when compared to previous years.

Meanwhile, the Peter W Beck precious metal refining division is now refining more platinum and palladium “than ever”.

“We have certainly seen those wishing to refine here in Australia directing these metals to us – platinum and palladium require specialist knowledge and techniques to recover,” says Ingham.

|

||

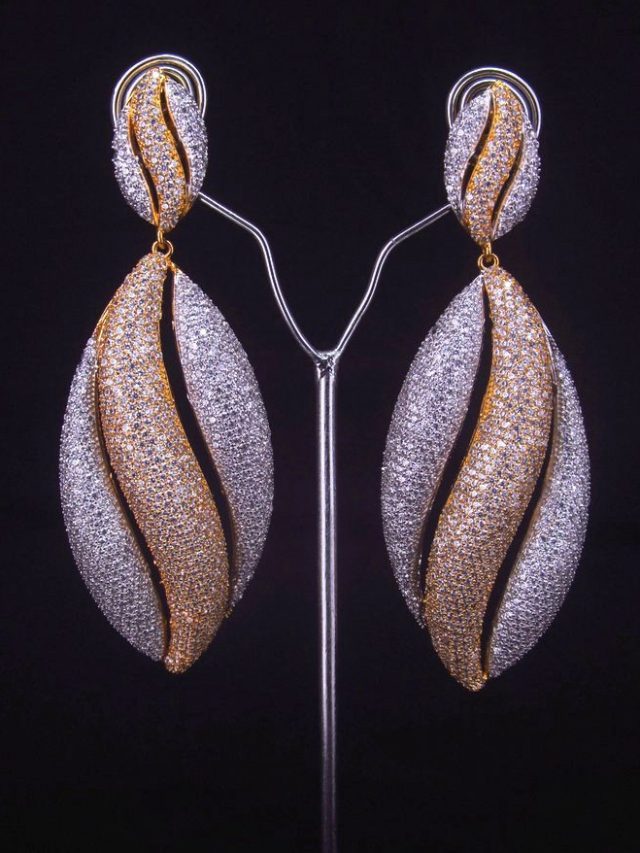

| From top: Nomination; Thomas Sabo; Van Cleef & Arpels | ||

|

|

|

|

Above: Roberto Coin |

Above: Bulgari |

Above: Cartier |

Silver in the spotlight

As the most affordable member of the precious white metal category, silver has consistently maintained a stable level of demand in the market.

Between 2010 and 2019, the year-on-year change in demand for silver jewellery averaged 5 per cent, compared with 9 per cent for gold jewellery, according to the World Silver Survey 2021 report published by The Silver Institute and Metals Focus, an independent precious metals research firm.

Worldwide, silver jewellery fabrication accounts for approximately one-fifth of worldwide demand for the metal and the Silver Five Year Forecasting Quarterly report, also authored by Metals Focus, predicts this will rise to a quarter of total demand by the mid-2020s.

From a manufacturing perspective, Botha says, “There has always been high demand for silver, and as a more affordable metal, it saw big growth in Australia [in the past year] due to many manufacturers bringing that production back on-shore to offset the shipping issues the world has endured since the onset of the pandemic.”

At Palloys, “scientific silver” – used for industrial, research, and medical applications – also led to an increase in demand for “high- end” refining services.

The Perth Mint’s Hayes observed a surge in demand for refined silver “investment products”, such as bullion, in the first and second quarters of 2021 due to a rally in the silver price – though he notes that the price per ounce has since “suffered several bouts of weakness in recent months”.

“Silver has been struggling to regain momentum, as growing concerns over the highly contagious Delta variant sparked a sell-off across industrial commodities,” he adds.

Silver prices remain relatively high from a historical perspective; it increased 137 per cent during 2020, compared with gold’s 38 per cent. Yet from a jewellery perspective, consumers Western markets such as Australia tend not to be influenced as strongly by fluctuations in the silver price – particularly when compared with gold.

Silver jewellery also enjoy other benefits; the World Silver Survey 2021 notes that the shift toward e-commerce is generally “positive as silver jewellery’s price points work well in an online space”.

This shift was pronounced in Australia over the course of the pandemic, with Australia Post’s 2021 Inside Australian Online Shopping report noting that e-commerce spending increased by 57 per cent in the 12 months to 31 December 2020.

Potentially indicating strong consumer demand for silver jewellery are recent financial results announced by Pandora, the world’s largest jewellery producer by volume.

The company refers to 925 sterling silver as its ‘signature metal’ and utilises an estimated 340 tonnes of silver per year across its product lines.

Pandora recently upgraded its forecast for the year, following promising financial results and citing a robust recovery in the US which is also the largest market for sterling silver jewellery by value.

In the Australian market, the silver and alternative metals jewellery category has seen double-digit increases in sales dollars every month from January to June this year when compared with 2020, according to data from Retail Edge Consultants.

Even taking into account the impact of the extended COVID-19 lockdowns across Victoria and NSW in July, Retail Edge’s data – drawn from more than 400 stores – indicated sales in this category were still 6 per cent higher than in July 2019.

However, the ongoing and unpredictable COVID-19 pandemic is likely to continue to weigh on both supply and demand for silver jewellery, and Ingham predicts that consumer tastes may also shift away from white metals in general.

“We have seen white metals enjoying popularity over the last three to five years, but in the cyclical nature of the market, we are predicting to again see popularity of yellow gold jewellery emerging in due course,” he tells Jeweller.

|

||

| Left to Right: David Yurman; Fope; Georg Jensen; Fope |

Generational appeal

While yellow gold has seen an undeniable resurgence in the market in recent years, some industry commentators have noted a generational divide of demand between Millennials and Gen Z, the latter of which appears to prefer white metals.

In a 2019 survey of 18,000 consumers across six international markets, the World Gold Council found that “gold jewellery resonates less well with younger consumers, most notably the 18-22 Gen Zs.

“The connection to gold’s emotional heritage is weaker among this group.”

Intriguingly, this trend was particularly pronounced in the Chinese market, with the report noting, “They are considerably less likely than Gen Z consumers in other markets to have bought gold jewellery in the last year – 18 per cent compared with 26 per cent globally.

“And only 31 per cent of them agree that wearing gold helps them to fit in with their friends, compared with 46 per cent at a global level.”

In contrast, Millennial attitudes toward gold jewellery were “not significantly different to those of older generations”.

Research conducted by Platinum Guild International found that younger Chinese consumers strongly preferred platinum jewellery.

“In China, platinum is most popular among Gen Z and Millennials aged between 18 and 45 – the future driver of jewellery consumption,” the report noted.

“Younger Chinese consumers prefer platinum in jewellery not only to signify relationship milestones such as engagement rings, wedding bands and anniversary bands, but in a range of non-bridal types of jewellery, such as fashion rings, necklaces, earrings and chains.”

These findings were echoed in De Beers’ 2018 Diamond Insight Report, entitled Millennials and Gen Z: Capturing the Opportunity, which noted that 96 per cent of bridal rings acquired by Chinese women contained platinum, while just 4 per cent contained gold.

Worldwide, white metals still dominate the bridal market. In the US, white gold remained the most popular choice for engagement rings at 45 per cent, followed by silver at 19 per cent, according to the De Beers report.

As Gen Z – currently aged between 11 and 25 – further ages into the engagement and marriage bracket, it is likely that white metals will continue to enjoy a competitive edge in the bridal category.

With thousands of weddings delayed by lockdowns across Australia, jewellers may be well-placed to take advantage with white metal offerings designed to cater to these consumers in the future.

In the meantime, the affordability of silver and its resilience and consistency add to the overall strength of the white metals category.

PRECIOUS METAL PRICES 2016-2021

|

Left, CHART A: Palladium |

|

Left, CHART B: Platinum |

|

Left, CHART C: Silver |

|

Left, CHART D: Rhodium |

|

Left, CHART E: Silver & Alternative Metals Sales – Jan-Jul 2021. Source: Retail Edge Consultants, ‘Jeweller’ analysis |

SPOTLIGHT ON

MIXING IT UP

A notable trend in the white metals market has been an emphasis on alloys and mixed designs in order to manage costs. “We have noticed that a lot more two-tone designs are being made, utilising rose and yellow gold for shanks and accents to lower the cost. However, the setting is always in a white alloy,” Chemgold’s Darren Sher tells Jeweller.” He adds, “With respect to this we have also observed a minor trend in mixed carat, such as an 18-carat yellow or rose gold shank with a 9 or 14-carat white gold setting, again to reduce cost for the customer but keeping a similar effect.” At Palloys, Botha observes, “The Fabricated Metals division of Palloys has always had a very large assortment of alloys on offer to a typically niche market, however, the introduction of the Alloy Properties pages on the new website, located under the Resources tab, have stirred up great interest in these ‘old-but-new-again’ alloys like palladium silver.”” Botha also notes an increase in demand for Argentium Pro 935, which combines 93.5 per cent silver with germanium to produce a low-maintenance, non-tarnish silver alloy that does not display firescale during production.” At Chemgold, the 18-carat white gold 18W132 alloy “continues to be very popular” given higher palladium prices. ” “With 13.2 per cent PGMs [platinum group metals] it is a very good alloy and on average 10 per cent less expensive than the traditional 18-carat white gold with 15 per cent palladium,” Sher explains.” “The metal is still premium white, hard wearing and great for polishing,” he adds. |

read emag

[ad_2]

Source link